Pawn Sacrifice

President Zelensky dumped an unpopular top aide, but his replacement isn’t any likelier to secure a fair deal from Putin or stamp out corruption

The axe finally fell on Andriy Bogdan, the politically compromised chief of staff to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky.

Bogdan’s volatile energy and theatrics served him well as manager of Zelensky’s populist campaign for the presidency but ultimately wore thin in a leadership role for an inexperienced team lacking cohesion. Bogdan clashed with Andriy Yermak, another Zelensky aide who was named as his replacement Tuesday after taking over the role informally weeks ago.

Veteran and astute observer of Ukrainian politics Yulia Mostovaya writes at ZN.ua that while Yermak is a smoother operator than Bogdan, neither man knows enough to help the actor-turned-president arrest the rapid and critical erosion of public institutions, the loss of central government’s control over the provinces and the deadweight drag of oligarchic schemes on the economy.

That is, neither could do it even if either wanted to. Mostovaya paints a devastating portrait of a leadership out of its depth, ignorant of the levers of government and regulation.

Beyond the unorthodox management style, what sealed Bogdan’s fate was his close association with former client Ihor Kolomoisky, the oligarch behind Zelensky’s unlikely rise from comedian to Ukraine’s first Jewish president.

Friends Like These

Kolomoisky’s brash talk and strongarm business tactics have made him a divisive figure in Ukraine. His pursuit of $2 billion in compensation over the nationalization of his bank, even as Ukraine’s central bank pursues the considerably more credible $3 billion counter-claim in London, has coincided with an arson campaign against the former central bank governor and the deployment of paid protesters tied to Kolomoisky to harass central bank officials and the executives they’ve placed in charge of his old bank.

Bogdan and another Zelensky aide had been implicated in directing government investigations to further Kolomoisky’s interests on recently leaked clandestine audio recordings. I described these in some detail in the last issue. The Associated Press story on Bogdan’s firing has a concise summary.

Kolomoisky has made plenty of enemies outside Ukraine as well. In his deposition for the U.S. House of Representatives impeachment inquiry, State Department official George Kent said President Trump’s opinion of Ukraine dimmed following a phone call with Vladimir Putin on May 3 and a White House visit by Hungarian strongman Viktor Orban 10 days later. “Both leaders, both Putin and Orban, extensively talked Ukraine down, said it was corrupt, said Zelensky was in the thrall of the oligarchs, specifically mentioning this one oligarch Kolomoisky,” Kent said.

Former National Security Council staffer Fiona Hill noted in her deposition that Putin has consistently used Ukrainian corruption to challenge the legitimacy of a sovereign Ukraine. But she also told U.S. lawmakers “Kolomoisky is someone who the U.S. government has been concerned about for some time, having been suspected and, indeed, proven to have embezzled money, American taxpayers’ money, from a bank that was subsequently nationalized, PrivatBank.”

Despite the howls of his many critics, Kolomoisky probably needn’t worry about immediate legal troubles in Ukraine. He remains Zelensky’s business partner, as Zelensky just noted in an interview in which he also said that “once I’ve put my trust in someone no one can convince me it’s the wrong sort of person, that he’s doing something bad or wrong. I have a hard time parting with people. In the same interview, Zelensky described his fight against corruption as having succeeded in barring bribe-taking “at the highest level” but not yet among “mid-level officials.” This Is a favorably narrow definition for Kolomoisky and the other oligarchs running sophisticated exploitative schemes embedded in legislation, regulation and the well-turned blind eye.

Over at NV.ua, contributor Sergiy Kuyun wonders when anyone in Zelensky’s administration or the government might do something about fact that Kolomoisky’s Privat Group took $1 billion out of the Ukrnafta refining monopoly it co-owned with the government five years ago, according to investigators from the National Anti-Corruption Bureau (NABU).

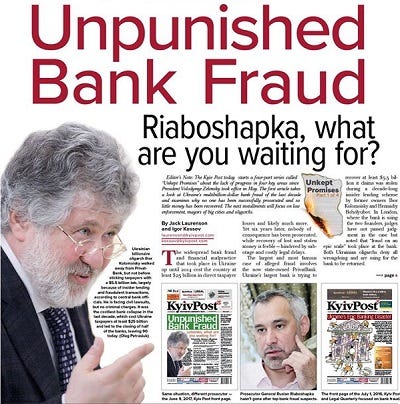

Meanwhile, my old love Kyiv Post, whose editor-in-chief called Zelensky “a phenomenal new face in a sea of tired old politicians” in March, is running a four-part series called “Unkept Promises” about his presidency. Part 1 is Unpunished Bank Fraud, which notes that bank bailouts including PrivatBank have cost Ukrainian taxpayers $25 billion since 2014.

For all that, Yermak’s rise as Zelensky’s chief of staff may still mark a watershed. As noted here on Feb. 3, he has been Zelensky’s international troubleshooter on sensitive matters like dealing with Trump’s circle and the accidental shootdown of a Ukrainian airliner in Iran as well as prisoner of war exchanges with Russia.

Russian Talks in Focus

He’s also the point man for Zelensky’s main foreign policy goal of negotiating an end to Russian occupation of eastern Ukraine. Amid tentative signs that both sides might finally be interested in a permanent settlement, Yermak has expressed hope that a deal might come in time to hold local elections in the occupied territories by the end of October.

The push for peace with Russia comes amid signs that the important U.S. relationship remains on the rocks despite the platitudes recently offered in Kyiv by U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo. He came a week after shouting to a reporter that Americans don’t care about Ukraine.

The day after that confrontation, a clandestine recording of a President Trump’s dinner with his associates revealed him musing about how long Ukraine might last in a war with Russia, essentially re-enacting the visionary Cosmo Kramer bit from Seinfeld.

“Without us, not very long,” he was told. And yet while Trump ultimately released the military aid he had ordered withheld, only last week Ukrainian officials complained about unexplained delays in the export licenses they need to buy an additional $30 million in U.S. arms and ammunition.

Even if that were not the case, even if Trump’s views on Ukraine remained better camouflaged, they were never really in doubt given his ideology. “A Europe whole, free, and at peace -- our strategic aim for the entirety of my foreign service career -- is not possible without a Ukraine fully free and at peace, including Crimea and Donbas, both currently occupied by Russia,” Kent said at his deposition. Trump doesn’t share that aim and siding with the weak against the dictators he admires isn’t his style.

Ukraine still matters enough to Trump that there are now U.S. prosecutors in Pittsburgh tasked with screening whatever Rudy Giuliani might “discover” next about Ukrainian corruption. But this interest might soon be history like Joe Biden’s presidential campaign.

(Regardless. it was probably not a great idea for Zelensky to do an interview with CNN’s Christiane Amanpour today in Munich that ended up contradicting Trump and providing visuals like the shot below.)

So Zelensky heads into peace talks with Russia with one of his sponsors, the U.S., retreating from the world in general, and from its backing from Ukraine under the impetus of its Putin-friendly president.

And the other crucial Ukrainian ally, the EU, will also be prodding it to cut a deal under pressure from a French president fed up with sanctions on a key customer for French technology exports.

Ukraine will be represented at these talks primarily by Yermak, widely seen as the Kyiv overseer for eastern Ukrainian oligarchs. Rinat Akhmetov and Dmytro Firtash were hurt financially by the Russian occupation in the east and the associated standoff, and would benefit hugely from a return to prior arrangements.

And Yermak will ultimately be answerable to Zelensky. When asked in the Interfax Ukraine interview this week about his first meeting with Putin in December (in Paris under the auspices of the ‘Normandy’ format also involving the leaders of France and Germany) Zelensky channeled George W. Bush’s infamous claim about looking into trustworthy Putin’s eyes and glimpsing his soul. “I’m certain he understood me, understood me very clearly,” Zelensky told Interfax Ukraine Tuesday. “When you have eye-to-eye contact you immediately understand what sort of person is in front of you. Despite all the intelligence reports to the contrary, it seems to me he understood me and understands the need to end this war.”

Putin almost certainly does, because not only would it get him out from under sanctions, but Kyiv will have to fund an economically ruined region still under his de-facto control and quite likely with an effective veto over any possibility of future EU or NATO membership for Ukraine.

Mostovaya writes that in her numerous private conversations with Bogdan, Yermak and Prime Minister Oleksiy Honcharuk, they frequently expressed loyalty to Zelensky, but never once mentioned Ukraine or country.

She concludes by likening the current leadership to the coronavirus: “A crown on the head while the country is governed by a colony of the simplest with a high likelihood of a lethal end for the host organism.”

All prior episodes of Ukrainian sovereignty were brought to a close with the collaboration of local elites. The hope that this time is different rests entirely on ordinary Ukrainians.